We had continued the meetings of the Center for Turkish Studies titled History Readings, which aim to read, understand and discuss the text, with 5 sessions of discussions on the Ottoman foundation after the readings of the Ottoman chronicles, which lasted for 31 months. The summary presentations of these meetings regarding both the Ottoman chronicles and the discussions on the foundation were published as a booklet in the BSV Notes series. In another controversial meeting we organized within the scope of the program, we addressed the Settlement Policies in Turkey from the Ottoman Empire to the Present. After an introductory session on the history of settlement in the Ottoman Empire, we talked about the individuals and their works that shaped the discussions in this field. In the last two sessions, we focused on the settlement and population policies in the Ottoman Empire in the 18th and 19th centuries with S. Faroqhi and Kemal Karpat. We wanted to briefly discuss these discussions, a comprehensive summary of which will be published in the BSV Notes series in the near future.

Roadmap of Türkiye’s Settlement Policies from the Ottoman Empire to the Present

First of all, let’s summarize the topics we covered in these five sessions:

- 1st Meeting:

- History of Settlement in the Ottoman Empire : An Introduction

- Presented by: Gülfettin Çelik, 22 October 2005.

- 2nd Meeting

- Ömer Lütfi Barkan and His Studies on Ottoman Settlement History

- Presented by: Yunus Koç, 21 November 2005.

- 3rd Meeting

- Cengiz Orhonlu and His Studies on Ottoman Settlement History

- Presented by: Tufan Gündüz , 26 December 2005.

- 4th Meeting

- Settlement and Population Policy in the Ottoman Empire

- Presented by: Suraiya Faroqhi, 13 March 2006.

- 5th Meeting

- Settlement and Population Policy in the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century

- Presented by: Kemal Karpat, 23 June 2006.

Evaluation: Kazim Baycar

History of Settlement in the Ottoman Empire: An Introduction

In the first of the series of meetings titled Population and Settlement Policies in the Ottoman Empire, our guest Gülfettin Çelik made an introductory presentation in the context of the sources and theoretical framework that can be taken as basis in the studies on population policies of the Ottoman Empire.

Çelik began his speech by emphasizing that the main lines of the Ottoman social system were parallel to other social systems, and he stated that in order to understand population policies, the conditions and basic assumptions that gave rise to the Ottoman social system should be examined, and he touched on the following:

If we consider the issue in the most general framework, individuals who have the same goals and pursue the same objectives form social groups. Social values emerge as a result of social groups coming together and entering into a certain relationship in order to fulfill the functions of purpose satisfaction and integration. In the next stage, the need for a system in these relationships leads to the emergence of institutional mechanisms. The emergence of institutions actually prepares the ground for a more comprehensive structure called a system. Once the mechanisms that constitute the social system, which consists of three subgroups: social, political and economic, have been formed, changing them can only be possible as a result of radical social and political formations.

The Ottoman Empire also includes all these elements that form the social system in general. In the Ottoman Empire, there are social groups, social values produced by these groups, institutions formed by these values, and systems created by these institutions. Apart from these, there are many other aspects that make the Ottoman Empire different from others. First of all, the Ottoman social system emerged with some preconceptions as well as some conditions imposed by the period in which it ruled.

In this context, it is possible to talk about four main factors that contributed to the Ottoman system. These are the Central Asian cultural heritage, Islamic teachings, the contributions of Anatolian civilizations and the needs of the age. The Ottoman social system is unitary and centralized in political terms, and while it prioritizes private enterprise in economic terms, it has an interventionist nature; in social terms, the state is also supervisory and directive. In addition, the absence of a social system based on classes can be considered among the distinguishing features of the Ottoman State.

In this context, it is possible to examine the Ottoman settlement and population policies in three separate periods: the establishment period, the period when the mechanism continued, and the period when the transformation problem necessitated transformation in the system.

The main political goal of the Ottoman settlement policies during the foundation period can be summarized as the establishment of the system and the export of the system to the newly participating elements. The main goal in the establishment of the system is to provide authority. In this context, the provision of the needs of the soldiers can also be shown as a goal in shaping the population and settlement policies. The main goal in the economic point is to increase new tax opportunities indirectly in line with the creation of new production areas. In addition to the expectations of the state from social groups, it also has expectations at a lower level that directly target them. It is necessary to evaluate the Islamization policies in this context.

In the second period, which we call the period when the mechanism was established, the Ottoman Empire had largely solved the system problem. The settlement policies implemented in this period emerged more due to necessary reasons. The settlement policies in Cyprus, which was conquered in 1571, are a good example at this point. The settlement policies implemented on the island of Cyprus were aimed at settling people who were assumed to be causing problems in the system.

The last stage in which population and settlement policies underwent change and transformation coincides with the wide time interval between the 16th and 19th centuries. During this period, new developments worldwide, especially geographical discoveries, made it necessary to change population policies as in all other policies of the Ottoman Empire. The most important visible change during this period was that important trade routes such as Tokat and Erzurum lost their former importance. As a result, we see that people migrated intensively from the countryside to the cities. The Ottoman administration, despite its unwillingness, had to develop a new mechanism to provide for the provision of these people who had accumulated in the cities during this period. This need for change and transformation reached its peak in the 19th century. Indeed, extraordinary political issues that occurred during this century, such as the Balkan Wars and the Crimean War, significantly affected the Ottoman population, and three and a half million people migrated to Anatolia from various regions. Despite these intense migrations and rapid population changes, according to Çelik, the Ottoman Empire was successful in integrating the new elements into the system. The most important reason for this success is the Ottoman’s fundamental assumptions and world perception that are not based on the class system.

Ömer Lütfi Barkan and His Studies on Ottoman Settlement History

In the second meeting, Yunus Koç, who summarized his works on the settlement policies of the Ottoman Empire during the foundation period, touched upon the document-centered working method and the problem-centered working method, which can be evaluated as two different schools or working methods in historiography, at the beginning of his speech. He emphasized that Ömer Lütfü Barkan, who has a pioneering place in Turkish historiography , is one of the rare scientists who can successfully use both working methods simultaneously and reflect them efficiently in his works.

According to Yunus Koç, when Barkan’s products in the field of history are evaluated in their entirety, it is seen that three basic factors shaped Barkan’s academic studies. The first of these factors is the influence of the Annales school of French origin. The most praised Annales school of the 1940s and 1950s made the greatest contribution to historiography by incorporating geography into historical research. Barkan, who closely followed what was happening in the field of history worldwide, was also in close contact with representatives of this school.

Secondly, Barkan was influenced by the state-centered approaches that emerged around the world on the eve of World War II. Especially in this period, the re-production of certain scenarios about Turkey in a political sense would cause Barkan to primarily prioritize the state.

The third important factor that guides Barkan’s work is his motivation to respond to the findings of Western historians such as Gibbons and Wittek on the establishment of the Ottoman Empire. While Gibbons tries to explain the transformation of a small tribe of four hundred tents into a huge empire with racial theory, Wittek puts forward the Gazi theory on this subject. At this point, he supports Köprülü’s thesis against both historians. Then, as the main opening, he emphasizes the settlement policies as a factor that Köprülü perhaps leaves out, which holds land and people together.

In the background of Barkan’s reactionary attitude towards Wittek and Gibbons, there is an initiative that aims to understand what is happening at the grassroots level outside of state or system discussions. The embodiment of this initiative emerges through his studies on how settlement is realized and how it is carried out. At this point, Barkan evaluates the integration of man with the land in three stages within the framework of the population and settlement issue.

The first of these stages is an intensive population transfer, both before and after the Mongol invasion, from the 1070s to the 1230s. At this point, Barkan attaches importance to Köprülü’s understanding, which emphasizes the organizational structure of the population (structures based on religion and sects) in the state formation process. However, he also goes deeper into the society and addresses much more concrete issues such as how people were settled in villages, how people who were newly settled in the land engaged in agricultural activities, and how the zawiyas and tekkes received a response from the grassroots during this period.

The second stage of the process of integration of man with the land is the settlement process. The issue of where the Turkish tribes coming from the east went as tribes or in which regions and on what basis they were settled by the central authority has not yet been clarified. It is known that the Seljuks followed a settlement policy that would ensure that they would not shake the central authority. Barkan started from the 16th century large population and land registers, which are his main field of study. And from there, he tried to illuminate the issue by extending backwards using the records of old and discarded registers.

The third and final stage of the process in question will end with political organization upon population pressure and subsequent settlement. At this point, what is meant by political organization is the process of tribes or clans becoming institutionalized over time and emerging as a principality and, in a broader sense, a political will. Based on Barkan’s writings, it can be concluded that he sees this process as a conscious, highly systematic, pre-calculated process whose results are known in advance.

Cengiz Orhonlu and His Studies on Ottoman Settlement History

In our third meeting, where we examined the Ottomans’ settlement policies for tribes within the framework of both Cengiz Orhonlu’s studies on tribes and his own studies on the subject, Tufan Gündüz began his speech by emphasizing that the subject of tribes is a field worth studying in terms of both folkloric history and ethnographic history, since many of us continue to be familiar with the concept of tribes even today. According to Gündüz, the issue of tribes, which Cengiz Orhonlu first addressed, has not yet been fully evaluated, despite the fact that it has been processed by many historians and detailed local studies have been conducted on it. It is also too early to conduct such a comprehensive study. The ability to fully comprehend the issue of tribes depends, first of all, on the quantity of field studies to be conducted.

When it comes to the issue of tribes and settlement, the most debated issue is whether the Ottoman Empire had a planned policy from the beginning in terms of transitioning the various nomadic tribes to settled life. Gündüz states that, contrary to the view put forward by R. Paul Lidner and accepted by many historians today, the Ottoman Empire had no concern for settling the tribes in any way. According to Lidner’s famous claim, the Ottoman Empire, which adopted centralization as its motto, hated the tribes because they were an obstacle to this great project and tried to make them settle down at all costs. In order to do this, it imposed heavy taxes on the tribes and tried to harass them.

According to Cengiz Orhonlu, the state, whose main purpose and priority was to collect as many taxes as possible and to provide for the people, did not care much about whether the tribes were settled or not. The state, which cared about the continuation of economic activities, granted the tribes the right to have the lifestyle they wanted as long as they paid their taxes and did not cause rebellion or anarchy, and did not pursue a planned settlement policy. On the other hand, the state took tribal life under complete control. By preparing different laws for almost every tribe, it determined one by one how the tribes would pay taxes; which plateaus they would go to, which routes they would follow and which wintering grounds they would go to, and established these in an order. In addition, the transition of a nomad to a settled life was subject to certain rules (such as building a house out of stone, living there for ten years). The main concern in all of these stems from the state’s desire to collect the maximum amount of tax that was set.

The problem between the state and the tribes began to show itself in the 17th century. Especially from this period onwards, as a result of the intensification of wars and a significant deterioration in the state order, the tribes’ obedience to the state weakened. The tribes, who gained the courage to act more freely compared to the previous periods, began to damage the villagers’ crops and even rebel against the state when necessary. Thereupon, a certain settlement policy was followed for the first time in this period and it was planned to settle the tribes that caused unrest in Northern Syria in order to control them.

According to Gündüz, the main issue that needs to be emphasized here is that the state only struggles with tribes that cause unrest, and has no problems with nomads who pay their taxes and are busy with their own business. When these measures taken in the 17th century did not work, the tribesmen who were intended to be settled in Syria escaped and entered the interior of Anatolia, and when they started to commit banditry in the places they fled to in order to make a living, the situation became even worse. In the 18th century, the state followed a different policy and made a plan to settle these nomads in the places they were located. However, this policy also brought some tribes face to face with serious poverty. The emergence of infectious diseases in the places they were located also caused the tribesmen to break up. As a result, those who could escape left their places, but those who could not escape negotiated with the state and reached an agreement.

Finally, in the 19th century, we see that the settlement, especially the settlement made by the İslahiye Firka, had a different character. The state, which had only had to confront the tribes economically in the previous two centuries, now faced them politically as well. For example, during the Mehmet Ali Pasha rebellion, the tribes settled in Çukurova, which was between the Ottoman and Egyptian armies in Anatolia, found the opportunity to act more freely and supported one of the two sides in line with their own interests.

Settlement and Population Policy in the Ottoman Empire

In our fourth meeting, where we hosted Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi, who is especially known for her studies on the early modern Ottoman period, we discussed the background of the issue through previously conducted and well-known studies on settlement and population policy in the Ottoman Empire. In this context, Faroqhi stated that settlement policies can be summarized through three different basic approaches.

The first approach belongs to Ömer Lütfi Barkan, who made the first studies on settlement policies. According to Barkan, the basis of the Ottoman population transfer from other regions was to strengthen the dominance in the newly conquered areas. It is also possible to read this as an indirect Islamization policy from a superficial perspective. However, according to Faroqhi, it is not that simple. In fact, not only the Muslim population was brought to Istanbul from outside, but also active non-Muslim populations such as tradesmen and merchants were settled in order to meet the basic needs of the city.

The second approach to the subject was developed by Cengiz Orhonlu. In his work titled Orhonlu Tribes Settlement Attempt, he stated that the Ottomans did not look favorably on the nomads and (unlike the Safavids) were wary of the nomads’ attempts to gain a share of political power. Therefore, the Ottomans tried to ensure that the nomads settled down as soon as possible. However, this attempt failed. According to Orhonlu, the main problem at this point was that the Ottoman administration was indecisive within itself. The nomads, who had tried to sustain their lives by animal husbandry until that day, faced the problem of hunger in the regions where they settled down rapidly and could not adapt to agricultural production as quickly, and as stated in archive documents, they began to cause unrest.

Münir Aktepe, in his studies in the 1950s, addresses the issue of settlement from its negative aspects. Aktepe is of the opinion that settlement policies are not based on the policy of settling people in a certain place, but on keeping certain groups of people flocking to the country away from certain places and not allowing them to settle in certain places. The measures taken to prevent the flow of people to Istanbul in the 18th century can be given as an example of this.

When we look at the background of these three general approaches in the 17th century, the first conclusion that comes to mind is that the settlement policy encountered serious resistance. Indeed, in Ottoman villages where a money economy was thought to exist, certain services were provided by village families in a certain order and in order to benefit from these services, it was necessary to be a member of that village community. Therefore, if foreign settlers coming from outside did not establish a relationship with the existing community, it was not possible for them to take part in and benefit from such services. The reason why people did not want to settle down in a sense was based on this.

In this context, studies conducted on the settlement policies in Istanbul and Cyprus using Ottoman archives provide us with enlightening clues about the reasons for the resistance of the people of that period against the settlement. For example, although it was promised that houses would be given to the people who came to the city free of charge after the conquest of Istanbul, this idea was later abandoned and rent was requested from the houses. Furthermore, as can be seen in the example of the engagement case between a local family and an exiled family within the Jewish community, the exiles never had a legal status with equal rights to those who had previously settled. For example, Şenol Çelik’s studies on Cyprus have shown that the Ottoman administration was unsuccessful in settling families on the island. The fact that the island was subject to a plague epidemic and a locust invasion, and that individuals and families who were a problem in society were generally exiled here, caused the families to resist. Despite all these material losses, status losses, infectious diseases and grain shortages, it is seen that the population of Istanbul was much larger than expected. Especially in the 18th century, The fez guilds of the 19th century officially recognized the right of grocers from Tunis and the Balkans to do their business in the city of Istanbul as long as they did not cause any trouble and did not disrupt the city and guild order.

In conclusion, it can be said that the Ottomans were less successful in their policy of settling the tribes than is stated in the documents.

Settlement and Population Policy in the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century

In the last session of this series, where we hosted Kemal Karpat, who is known for his studies on the Ottoman population both at home and abroad, Karpat, who especially focused on population studies within the framework of the 19th century, focused on important issues such as the population flow to Anatolia that started in the early years of this century and gained momentum later, which regions the immigrants came from, how the immigrants were guided by the state and how they were settled.

At the beginning of his speech, Karpat emphasized that the Turkish nation has a migration history on Anatolian lands dating back even before Malazgirt, and argued that the issue of migration and population constitutes the axis of our existence as a nation. According to Karpat, throughout their history, Muslim and Turkish communities have been in a constant spatial mobility in one way or another. From this perspective, in order to understand our current society as a whole and to grasp the basic dynamics that hold it together, the issues of migration, population and settlement need to be analyzed well. Karpat sees the quantitatively very few studies on the Ottoman population as a serious deficiency and states that he has addressed the issue with these basic concerns.

Throughout the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire accepted immigrants, mostly Turks and Muslims, who had to migrate from Crimea, the Caucasus and the Balkans as a result of completely new political conditions. Although migration from Crimea to Ottoman lands increased after the Russians took control of these lands in 1783, since the Crimean Tatars coming and going to Anatolia was a very common occurrence in previous periods, the Crimeans did not see the Anatolian people, who spoke their own language and had their own religion and nation, as foreign to them. The Crimean people, who were intensely attached to their own religious and national identities, migrated to Anatolia intensively from 1873 onwards in order not to remain under Russian rule, which they saw as foreign to them.

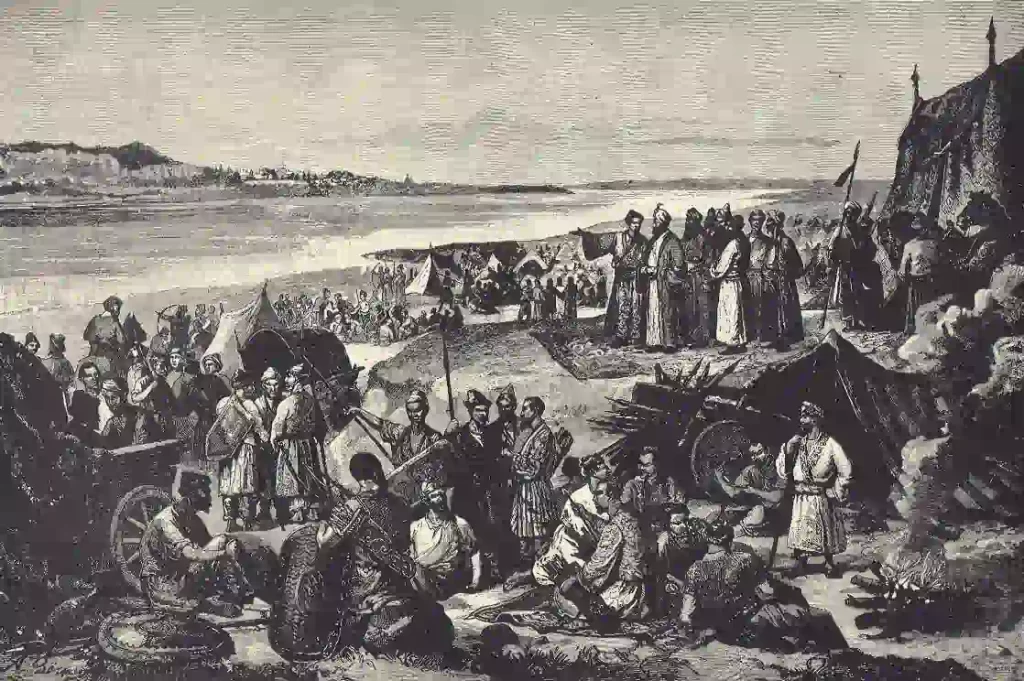

When followed chronologically, the second important wave of migration to Anatolia was the Caucasian migration. With the end of Sheikh Shamil’s 25-year resistance against the Russians, the Caucasus came completely under Russian control. As a result of the forced migration of the people here as a precaution against a possible attack from the Caucasian front with the beginning of the Crimean War, a great variety of Muslim Caucasian people, speaking thirty to forty different languages and numbering one and a half to two million, migrated to the Ottoman Empire between 1862 and 1924. According to Karpat, this forced migration was a complete disaster. According to his calculations in the British archives, approximately 800 thousand Muslims were massacred during this deportation.

The beginning of the Balkan war in 1877 was also the harbinger of the third major wave of migration to Ottoman lands. The Balkan states gaining their independence one by one created security problems for the Muslim population that had a serious presence there. As a result of this problem, nearly one million immigrants came to Anatolia.

These three major waves of migration seriously affected the social and demographic structure of Ottoman society. In order for the immigrants to be settled in a healthy way and to be able to continue their lives, the Ottoman administration wanted to implement a systematic settlement policy and for this purpose, as a first step, it established a settlement commission of experts. The Ottomans preferred to settle the large immigrant masses that came to their country by dividing them into smaller groups. The state’s greatest concern here was undoubtedly security. In fact, the leaders of these large masses were deliberately settled in the center and an attempt was made to take them under control.

The Ottomans settled the immigrants on lands suitable for agriculture but not cultivated, which constituted approximately 50% of the state according to a study conducted by Mithat Pasha. The immigrants provided significant tax revenue to the state and contributed to general production with the agricultural activities they carried out here. Indeed, by the end of the century, the amount of taxes the state received from agriculture had increased three to four times. In addition, the newly arrived population made a significant contribution to the army in terms of providing soldiers.

As a result, these migrations to Anatolia during this period enabled the formation of a brand new society by merging with the existing local structure. According to Karpat, the strongest nations are those that are formed from such a mixture. These migrations changed the old Ottoman society, gave it new blood, new life and opened a new horizon.

Karpat concluded his speech by stating that the migration from rural areas to cities in Turkey, which started in the late 1950s, reunited the population and created today’s Turkish society.

The History Readings series continues with the subject of “Byzantine Chronicles” after “Settlement Policies in Turkey from the Ottoman Empire to the Present Day”. We hope to see you in these very important and interesting meetings where the texts and people that shaped the discussion will be discussed as in the previous programs.